In the News

Detroit — A growing number of Iraqi refugees are attempting to “save their own lives” by cutting off their tethers to evade immigration authorities’ deportation attempts before their court cases are heard, families and lawyers say.

At least seven Iraqi nationals have removed their tethers in Michigan in the last month, according to a lawyer representing 23 refugees.

One of them, Ali Al-Sadoon, ditched his tether in July in Detroit on the day he was supposed to be deported. The 33-year-old refugee from Redford Township now faces criminal charges for removing the ankle GPS tracker in addition to removal orders for breaking and entering, for which he was sentenced in 2013.

“The only reason Ali cut his tether was because he was scared … they sentenced him to death.”

BELQIS FLORIDO, ALI AL-SADOON’S WIFE.

But his case is expected to head to a trial he might not have otherwise received.

“The only reason Ali cut his tether was because he was scared …” said his wife, Belqis Florido. “They sentenced him to death.”

Last week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials also arrested Wisam Hamana, 39, of Hazel Park and Baha Al-Said, 35, of Ann Arbor after both cut their tethers. Another Iraqi national, Oliver Awshana, 31, was deported from Calhoun County Correctional facility and made such a scene while transferring flights in Chicago The ACLU of Michigan has argued in federal court, where the detainees’ fates have played out for the past two years since immigration raids in June 2017, against repatriation to Iraq because, it says, if the men are sent back, they face torture or death because of their Christian faith, for having served in the U.S. military or for seeking U.S. asylum.

Shanta Driver, an attorney representing 23 Iraqi nationals, said the refugees cut their tethers because they “get to a point of desperation.”

Driver said the men have spent most of their lives in the U.S., bearing children and working — establishing roots.

“A lot are still in shock and still can’t believe this is happening to them,” Driver said. “(Al-Sadoon’s case) is as close to a death penalty case as I have ever had. His brother returned to Iraq and was killed.”

“A lot are still in shock and still can’t believe this is happening to them. (Al-Sadoon’s case) is as close to a death penalty case as I have ever had. His brother returned to Iraq and was killed.”

SHANTA DRIVER, AN ATTORNEY REPRESENTING 23 IRAQI NATIONALS FACING DEPORTATION

The men are being deported for committing crimes that the government believes violate U.S. immigration laws. They are more vulnerable to deportation after being released from detention because their immigration cases were denied and they are seeking emergency stays so they can appeal their cases. ICE, meanwhile, is expediting deportations before that can happen, Driver said.

ICE officials said cutting off the tethers has forced the agency to detain the men again and file federal charges for the act.

“Removing GPS tracking devices could expose aliens to violations of their reporting requirements, federal criminal charges and prolonged detention,” ICE said.

The ACLU and ICE officials declined to comment about how many detainees are taking unusual measures to avoid deportation or if removing the tethers is unique to Michigan.

Al-Said’s fiancée, Reema Ali, was with him when ICE officials found him in Ann Arbor on July 30. Al-Said was granted refugee asylum at age 11. Al-Said is being deported after pleading guilty in 2013 to delivery of marijuana and home invasion charges. He is being held at Calhoun County in Battle Creek for cutting his tether July 14 and is expected to be deported on Sunday, his fiancee said.

“After he leaves, I’m going too,” Ali said. “I don’t have any kids, which makes it easier for me to go with him, but I have to leave my siblings and parents. That makes it so hard. I have to miss out on my nieces and nephews growing up.”

The family said when Al-Said’s brother was deported 2015, he was kidnapped. The incident filled Al-Said and his family with fear, which led him to cut the tether, Ali said.

“He didn’t want to leave his family especially because he’s the only support,” she said. “After he cut his tether, Baha’s dad was hospitalized for a week, suffering from a panic attack and mental illness, thinking he’d lose another son.”

Similarly, Al-Sadoon was arrested at his home in Redford July 26 by ICE officials who were “busting down the door and holding guns pointed” at him while his six children were holding on to him, said his wife, Florido. He is being held in Sanilac County Jail. He, too, fears for his life if he’s sent back to Iraq.

“There was like 15 officers all holding AR-15s outside my house, and I asked them to show me a warrant, but they just kept screaming open the door,” said Florido, who recorded part of the incident on video. “All the kids were holding on to Ali and then you heard boom, and they’re running towards us with guns pointed, screaming at him to stop resisting when he was on the floor holding his child.”

Driver and Florido said in 2010, Al-Sadoon’s brother, like Al-Said’s, was kidnapped at the airport in Iraq.

“They haven’t heard from him since,” Florido said. “His father was also killed and Ali missed his burial while being held in immigration custody for three years.

“He was never able to reopen his (immigration) case … I’m working on our passports because if they try to deport him to his death, they’ll be sending all of us.”

ICE had a different version of events in Al-Sadoon’s recent arrest. ICE spokesman Khaalid Walls said Al-Sadoon ran inside the home and barricaded the doors with furniture and appliances. He said when agents identified themselves with an arrest warrant, they refused to open the door, so agents forcefully entered.

that the pilot refused to fly him, his lawyers said.

“Mr. Al-Sadoon’s re-arrest and now pending federal criminal charges should make clear that these actions are not without consequence,” the agency said.

Outcry for stays

Some refugees are fighting their deportations “by any means necessary,” said Kate Stenvig of Detroit’s BAMN, an advocacy coalition defending immigrants’ rights whose law firm is representing some of the refugees in court.

Oliver Awshana, who lived in western Michigan and was granted refugee asylum in 2006, is being deported after pleading guilty in 2017 to a drug-related charge. Stenvig said ICE officials lied to Awshana, saying he was going to be released from detention in Calhoun County, where he was being held.

Officials said they would send him to the Detroit field office for a tether, after which he’d be released on supervision while waiting to reopen his immigration case. Instead, Awshana was immediately taken to Metro Airport, she said.

When the plane landed in Chicago, ICE was transferring him to a Turkish airline flight when Awshana began screaming.

“He was snatched up and deported. No one knew until I got the video. It’s a war zone there.”

HADEEL KHALASAWI, LONG-TIME FRIEND OF JIMMY AL-DOUAD

“Oliver Awshana screamed and yelled and told everyone around (that) he was being deported to his death until the pilot refused to fly him,” Stenvig said. “They had to take him to the hospital because they roughed him up getting him off the plane. He was returned to Michigan to Calhoun, and we got his case reopened.”

Awshana and Al-Sadoon’s attorney, Driver, told judges that families need more time to prepare for deportation. She said ICE puts families in a position by informing them of deportations late on Fridays after the courts have closed and no appeals filings can be addressed, and schedule them to be at the airport by Sunday.

“There isn’t time to act. We need to give the court a 72-hour notice of their deportation, and we’re often not informed until hours before someone’s flight,” she said. “(Awshana’s) decision to try to get off the plane worked because now he’s in a much more protected place and we have time to prepare his case.”

Others have faced different difficulties. In July, five Iraqi refugees were detained inside the Detroit ICE Field Office on Jefferson Avenue after arriving for their routine appointments or to fix their tethers.

One of them, Nashat Butris of Hazel Park, was already deported, according to ICE.

Last month, Jimmy Al-Daoud of Shelby Township, who came to the U.S. as a 6-month-old, was deported to Iraq after being sentenced on drug possession charges, according to his family. He was deported with two others, and they lived together on the streets of Iraq.

Al-Daoud, 41, was found dead Tuesday by one of the other men, said Hadeel Khalasawi, a long-time friend who lived next door in the township. The deported men phoned the family friend to break the news.

It’s unclear what caused Al-Daoud’s death. He sent Khalasawi a video a month before where he spoke of the difficulties of being unable to get insulin for diabetes or find shelter.

“He was snatched up and deported. No one knew until I got the video,” said Khalasawi, who was also picked up in the 2017 raids. “It’s a war zone there.”

Not the first act of protest

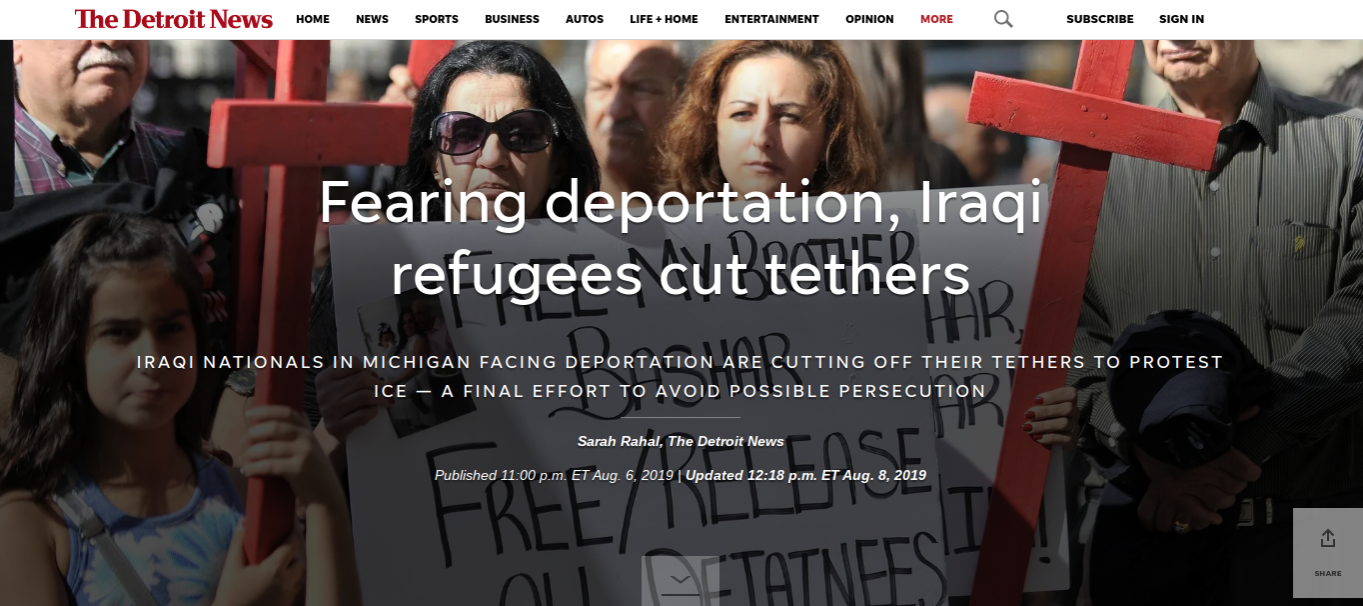

The refugees have tried various methods to push back against their detentions and deportations. In September 2017, some Iraqi detainees swept up in the raids went on a hunger strike, saying they would rather die closer to their families than be deported.

Since May 2015, volunteers for the nonprofit Freedom for Immigrants have documented 1,396 people on hunger strike in 18 immigration detention facilities.

Families of the Iraqi detainees continue to protest in Sterling Heights, Warren, Dearborn and in front of Detroit’s federal courthouse to call for their release.

They petitioned and wrote letters during Christmas to judges to free their fathers and brothers, and called lawmakers for their support.

“Protesting with other families wasn’t just about making noise. Those protests were about saving hundreds of lives,” said Ashourina Slewo, whose father was detained for nine months and now awaits his immigration case to determine his stay in January 2021.

“We were fighting for them because they had been caged and suppressed from being able to do so themselves. I wish I could say I never saw this happening to my family or my community,” she said.

Hamama v. Adducci

Many of those targeted are plaintiffs in Hamama v. Adducci, a nationwide class-action lawsuit brought by the ACLU of Michigan in 2017. The ACLU lawsuit was filed after more than 1,400 Iraqi nationals nationwide — 114 from Michigan — were swept up in the 2017 raids.

The raid followed President Donald Trump’s executive order barring admission into the United States of nationals from seven countries, including Iraq. Detainees were being held in correctional facilities while it was uncertain if Iraq would accept repatriated detainees at that time.

Some Iraqi nationals, including Al-Sadoon, were released in December after years in detention based on the ruling by U.S. District Court Judge Mark Goldsmith, who said ICE could not indefinitely detain foreign nationals while seeking to deport them.

“The State Department has evacuated all non-essential American personnel from Iraq because it is so dangerous, yet the administration is simultaneously trying to deport longstanding members of our community to Iraq, even though they face persecution, torture and death,” ACLU attorney Miriam Aukerman said. “… A fair process takes time, which is why it is so critical that Congress pass the bipartisan bill to pause Iraqi deportations. Many Iraqis have won their immigration cases, but they need time to do so.”

A bipartisan group of lawmakers hopes to help their cases with a bill that would grant Iraqi nationals relief from detainment and deportation while they await individual hearings before immigration judges. The bill would exclude those who pose a threat to national security. Democratic U.S. Rep. Andy Levin of Bloomfield Township and Republican Rep. John Moolenaar of Midland are spearheading the bill backed by 30 lawmakers across the country.

Michigan’s 9th District, represented by Levin, has the largest Iraqi-born community of any congressional district in the country, according to census data. Levin said they sent letters to Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and are working with the executive branch requesting intervention.

Will rebelling help their cases?

Jonathan Weinberg, an associate dean of research and professor at Wayne State University Law, said ICE has consistently sought to ship people out in advance of court rulings since the initial round-up in June 2017.

“I’d characterize cutting one’s tether and going AWOL or disrupting a deportation flight not so much as an act of protest, but rather as a simple attempt to win another day or two in the country so that the court can rule, and hopefully issue a stay,” he said.

While she can’t say if cutting tethers or other acts of protest are helping, Driver said she’s having more success reopening immigration cases.

Sabrina Balgamwalla, director of the Asylum and Immigration Law Clinic at WSU, said the methods might be contributing to the larger conversation about immigration in the United States.

“It depends on what other options the person has, the severity arising from charges, whether major or no consequences … it’s hard to say if these actions help or hurt cases because it may keep some cases alive, but if the judge has already ruled on their stay, it’s not going to change,” the assistant law professor said. “Then again, there’s the acts of … resistance that’s contributing to a larger conversation about where the direction on immigration policy is heading.

“… And no one can argue that these repatriations are happening voluntarily.”

srahal@detroitnews.com

Twitter: @SarahRahal_